Disc disease

Disc disease

Disc disease is a common problem in dogs and relatively uncommon in cats. There are two major categories of disc disease, Type I and Type II. Type I disc disease is characterized by disc herniation ("slipped disc") and a sudden onset of signs. This type of disc disease occurs in dogs and cats of any age or breed, but is seen most commonly in short-legged breeds (e.g., dachshund, bassett hound, shih tzu, lhasa apso, corgi, pekingese), and some other small breeds such as the poodle and cocker spaniel. It also occurs in larger breeds of dog, such as doberman pinschers. In order to understand what happens in animals with disc disease, a little understanding of the anatomy of the back (spinal column) is required.

The back or spinal column is made up of a series of small bones called vertebrae. The vertebrae are lined up like blocks and the spinal cord passes through a hole in the center of each vertebra. The spinal cord is very important, as it carries messages from the brain to the rest of the body. The spinal cord is also extremely delicate and the tunnel formed by the surrounding vertebrae helps to protect it from damage. Between each vertebrae, just under the spinal cord, lies a circular cushion called the intervertebral disc. These discs cushion the vertebrae from one another, acting like shock absorbers and also providing flexibility to the spine.

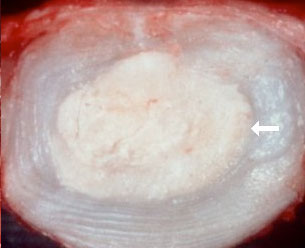

Intervertebral discs deteriorate as part of the normal aging process. Some breeds of dogs such as dachshunds, may undergo disc degeneration earlier in life. Normal discs are made up of an outer fibrous ring and an inner gelatinous center [similar to a Tootsie-Pop®(firm on the outside and soft in the middle)]. With age the disc changes and the outer ring often tears and the inner soft center of the disc hardens and may even calcify. A time may come when the torn outer ring may no longer be able to hold this hardened center in place and movement of the vertebrae may suddenly push the disc out of its normal position. This is called disc herniation (or "slipped disc"). When disc material herniates, it may be pushed out the side, below, or up around the spinal cord. Herniation of the disc often occurs very explosively, causing significant injury to the spinal cord and pain to the animal. There is very little room between the spinal cord and the surrounding bony vertebrae and as a result, once disc material has herniated into this small space it continues to cause damage to the spinal cord.

The areas of the spine most commonly affected by herniated discs are the neck, and the mid- to lower back regions. Common signs seen with herniated or "slipped" discs include: Back pain, lameness, incoordination, and/or inability to walk in the hind legs, or all four limbs. Animals that are unable to walk may also be unable to urinate on their own. Although these signs indicate that the dog or cat has a problem affecting the spinal cord, they do not indicate the specific area that is affected, or the cause of the problem. Tumor, fracture or infection involving the vertebrae or spinal cord may all produce neurological signs similar to a herniated disc. Further diagnostic tests are needed to determine the exact location and cause of the problem and to determine appropriate therapy.

In order to determine the exact location and cause of the problem, the animal must first be examined. The results of the neurological examination help the veterinarian to determine which part of the spinal cord [upper neck (C1-5), lower neck (C6-T2), midback (T3-L3), and lower back (L4-Cd)] has been affected. General anesthesia is needed for further testing. Prior to anesthesia blood and urine tests, and possibly chest radiographs (x-rays) and/or abdominal ultrasound are done to make sure that the dog or cat is otherwise healthy and has no other problems that may increase the risk of anesthesia. Once these tests have been completed the patient is anesthetized for radiographs (x-rays) of the entire spinal column followed by a special radiographic study called a myelogram. A myelogram is an x-ray study in which a special dye is injected into the spinal fluid surrounding the spinal cord.

The myelogram allows any disc material pushing against the spinal cord to be seen on the x-rays. As a part of this procedure, a sample of spinal fluid (spinal tap) is also collected. Analysis of the spinal fluid helps to rule out other causes of spinal problems such as infection.

Most animals with disc disease need surgery to remove the disc material compressing the spinal cord. Sometimes an animal with disc disease does not undergo surgery, but instead is treated with strict rest, which is accomplished by means of confinement to a cage. In general, this approach is used for a first attack of back pain and in animals that do not have problems walking. Strict cage rest does not relieve spinal cord compression, but it may help to reduce some of the pain and swelling around the spinal cord, and give the torn outer rim of the disc time to heal. It is not uncommon for animals treated this way to suffer repeated attacks of pain, lameness and paralysis, as often more disc material herniates and places additional pressure on the spinal cord. Each episode of disc herniation may cause additional permanent damage to the spinal cord. Surgical removal of disc material from the spinal canal is the treatment of choice. Surgery provides the most rapid and best recovery of spinal cord function, and is the recommended treatment at the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital(VMTH) at UC Davis.

The administration of cortisone (and other steroids) to animals with disc disease is controversial. Current scientific evidence does not support the use of cortisone, although it's use is widespread. The adverse effects of cortisone (e.g., stomach ulcers, vomiting, diarrhea) must always be considered, particularly in animals who cannot walk or who have trouble walking. Animals who cannot walk are predisposed to the adverse effects of cortisone, which may be life threatening.

Animals with disc herniations in their neck may require a similar surgery called a ventral slot, which is done from the underside of the neck. Spinal surgery is very difficult and ideally should be done by a specialist, a neurosurgeon or surgeon. At UC Davis, most animals with disc herniations of the midback undergo a special type of laminectomy, called a hemilaminectomy, whereby only one side of the vertebrae is removed. In conjunction with the laminectomy, most animals at UC Davis also undergo fenestration of the discs in front of and behind the one that has herniated. In order to fenestrate a disc a small window is made into the outer fibrous ring of the disc, and the material in the center of the disc is removed. Fenestration is done to reduce the possibility of the surrounding discs from herniating and causing the animal problems in the future.

The most common surgery done to remove disc material from around the spinal cord is called a laminectomy. The spine is approached through an incision in the middle of the back and using a special drill, a window is made in the bone of the vertebra immediately above the disc. The disc material underneath the spinal cord can then be gently removed.

The speed of recovery from surgery and the extent of recovery of normal function (e.g., walking) is dependent on many factors, including how fast the disc material hit the spinal cord, the degree of the damage sustained by the spinal cord and the length of time that the spinal cord has been compressed by the disc material. In general, animals exhibiting severe neurological signs (e.g., lack of sensation in their toes), a rapid onset of signs (hours or less), and/or a long period of time before surgery have a prolonged recovery period. The more severely affected animals may have varying degrees of permanent damage. Fortunately the majority of animals with disc disease that undergo surgery recover function to their limbs relatively quickly and completely.

At UC Davis, animals are usually hospitalized for about 3-10 days after surgery. They are generally discharged from the hospital once they are comfortable and are able to urinate on their own. Once home, the patient's activity is restricted for 4-6 weeks. Skin sutures are generally removed 10-14 days after surgery by the referring veterinarian or by the neurosurgeon at UC Davis. Patients are generally rechecked at UC Davis 4-6 weeks after surgery to assess recovery or earlier if any problems or concerns develop.

While most animals requiring surgery for one disc herniation do not suffer additional disc herniations, a small number of animals do. Therefore, it is very important that as many predisposing environmental factors be controlled as is possible. Owners are encouraged to institute weight control management to prevent obesity, start non-concussive exercise to promote fitness, eliminate stair climbing and to stop jumping behavior once recovery from the disc herniation has occurred. Since disc disease has been proven to be inherited in some breeds and suspected in others, breeding of animals that have suffered from disc disease is not recommended, and neutering is encouraged.