Lessons from the Pandemic: Q&A with Dr. Jonna Mazet

by Cody Kitaura for UC Davis Magazine

After the coronavirus pandemic, humans will face continued concerns about our vulnerability to new illnesses. In fact, we’ll need to take the lessons learned from our collective response to COVID-19 and use them to make sure future pandemics aren’t as devastating, two infectious disease experts said in separate interviews.

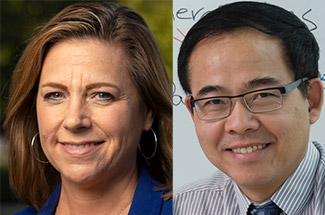

Jonna Mazet ’90, D.V.M. ’92, M.P.V.M. ’92, Ph.D. ’96, a professor of epidemiology and disease ecology at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, and Linfa Wang, Ph.D. ’86, a professor of emerging infectious diseases at Duke-National University of Singapore Medical School, have collaborated on PREDICT, a project directed by Mazet to bolster emerging disease detection around the world, but the two otherwise do separate research on opposite ends of the globe. PREDICT’s grant funding from USAID was scheduled to end this spring, but it was funded for an extra six months to assist with COVID-19 research. Wang’s research centers on bats and the reasons why those animals are able to safely co-exist with so many viruses that end up being deadly to other species; more recently his work has focused on tracing the origins of COVID-19.

Jonna Mazet ’90, D.V.M. ’92, M.P.V.M. ’92, Ph.D. ’96, a professor of epidemiology and disease ecology at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, and Linfa Wang, Ph.D. ’86, a professor of emerging infectious diseases at Duke-National University of Singapore Medical School, have collaborated on PREDICT, a project directed by Mazet to bolster emerging disease detection around the world, but the two otherwise do separate research on opposite ends of the globe. PREDICT’s grant funding from USAID was scheduled to end this spring, but it was funded for an extra six months to assist with COVID-19 research. Wang’s research centers on bats and the reasons why those animals are able to safely co-exist with so many viruses that end up being deadly to other species; more recently his work has focused on tracing the origins of COVID-19.

UC Davis Magazine asked the two experts how the COVID-19 pandemic will change the way the public views their field and what lessons we need to take from it. These interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

In a normal year, people might not pay much attention to this kind of research. How do you get people to pay attention to this kind of research before your subject turns into a global pandemic?

Jonna Mazet: It was certainly much harder before. The scientific and health communities were interested and concerned, but the general public and policymakers were not as concerned as we had hoped. We need to do a better job communicating and making data accessible. I just hope right now we can harness this energy and concern for the world to be looking forward rather than backward. If we don’t change and look forward and be ready for the next one, we will be victims of “Disease X” again.

Linfa Wang: It’s fair to say the attention has been 10 times if not 100 times more this year than a normal year. My function is to look into bats, which is always newsworthy. The science gets so much attention, the granting bodies all want to give you money. It’s a very surreal experience. For emerging infectious diseases, our field is different. [It’s like preparing a military, except] you don’t get a peacetime. In peacetime people think an army is useless, but you cannot build up an army and train them in one day. Money is no concern, but people tend to forget during peacetime that you need to get everything ready before the pandemic.

What can COVID-19 teach us about infectious diseases in general?

Mazet: It’s important to recognize what went wrong here — that is, that we didn’t have a unified plan that was supported both scientifically and politically. We need the country to be trusting scientists and have access to the information from scientists, and we need our leaders to work together with scientists to be ready and be prepared when something comes along. We have all of the capabilities to be able to do that, but we need better interactions between government, academia and policymakers.

Wang: The lesson from COVID-19 is very clear. Science has advanced so much in the 17 years since SARS, and yet we still failed to contain it. Scientists alone or doctors alone cannot be effective; we need the politicians and backers, as well as international transparency and cooperation. We do need an international “police” for unknown viruses, no matter where they start. We need one international body, and currently the World Health Organization is best suited. We need an international organization with unlimited access and the power to go in, investigate and contain. Without that, COVID-19 will not be the last pandemic.

What will the next pandemic look like, and how will our response be different because of COVID-19?

Mazet: I’m advocating for the world to come together to address the huge [library] of viral information and discover what is available to be discovered. That is completely achievable [through programs like UC Davis’] Global Virome Project, which brings together nations without regard for national boundaries or scientific credit. We know now because of the PREDICT Project what that would cost and it’s one-tenth of a big outbreak and miniscule in comparison to the trillions we’re spending on COVID-19.

Wang: Nobody can predict how next pandemic will look. To execute this kind of plan we need political will and international leaders. This is what’s missing in COVID-19. The next time will not be much different. It will start from some city. Pandemics can start from anywhere in the world. In terms of how we can respond differently, we need an international body that has the power and financial backing to get to the front line within days, and be transparent and politically neutral. Without that framework I don’t see how we can do better.

What will finding the origins of COVID-19 teach us?

Mazet: Learning the origins of COVID now is critically important because we need to prevent ongoing infections. There are susceptible hosts and reservoir hosts. We don’t want to be fighting this same virus forever. We might miss the opportunity to control the seeds of infection that could get started or could already be out there. Understanding the origins is incredibly informative for other viruses that travel along these same pathways.

Wang: In all the disease outbreaks, if you don’t know the origin and don’t know how the early origin outbreaks happened you cannot produce a strategy for the next outbreak. It’s academically important [but] more important [for] public health.

Why is international cooperation important?

Wang: COVID-19 is a perfect example. … I try not to point fingers, but we all need to do better. There are politics at the beginning of any unusual infectious disease event. If we’re non-political we can be 100 times better. I can be very confident about this, but I don’t have a clear pathway or power to install this before the next pandemic. Bill Gates is powerful and has money, but he cannot solve the cross-border issue. No. 1 is for the U.S. to go back to the WHO. [Note: The Trump administration notified the agency of its intention to withdraw and pull funding in July; President-elect Joe Biden has said he will rejoin.] The founding model of the WHO may be that we need to have a different funding scheme for pandemics so that we always have a well-funded, multi-disciplinary team ready to go — like the military analogy.

Mazet: We know from the PREDICT project — we had discovered over 100 coronaviruses and had been waving the flag that coronaviruses are out there in rich pools to infect people. We documented the human food chain, especially wildlife trade and trafficking, was high risk. We documented that in multiple countries: China, Vietnam and elsewhere. Now we have an example of what can happen — it’s not theoretical. We can never have a million people die again because [people] ignored [our warnings]. Putting that together can really help us prevent the next one.