The Virus Detectives: How Dangerous Is a Hidden Infection in Red Pandas?

When researchers announced the identification of a novel virus in captive red pandas in the journal Veterinary Pathology last year, the discovery raised more questions than it answered. Does this virus pose a health risk to affected pandas? Is it widespread among captive populations? Where did the virus originate and how might it impact the breeding management of this endangered species?

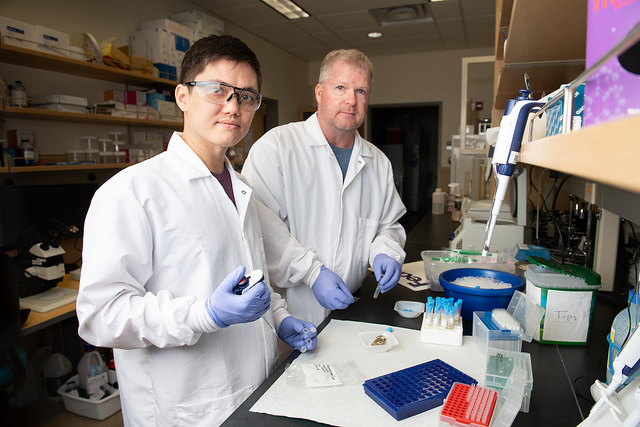

Those are the questions now being addressed by Dr. Charlie Alex, a research pathologist in Dr. Patty Pesavento’s virology lab. Pesavento is a pathologist and viral disease expert with a penchant and strong track record for discovering novel viruses. For the past several months, Alex and Ken Jackson (a molecular biologist in the lab) have been analyzing fecal samples brought to UC Davis from pandas in zoological institutions across North America. To date, the lab has tested about 100 individuals from about 35 different zoos; approximately 30 percent have tested positive. It remains unclear what kind of health risk this virus poses to those affected.

The first example of this new virus was uncovered during a routine necropsy of a geriatric red panda from the Sacramento Zoo conducted at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine in 2015. For more than 30 years, the zoo has relied on a collaboration with the school to assist with the healthcare of their animals. In this circumstance, the red panda was the second oldest of his species on record and the diagnostics performed when he was ill had not indicated a viral infection. However, based on necropsy findings, the pathologists were still highly suspicious for a viral infection, even though diagnostic testing had ruled out the most likely suspected viruses.

This was a case for virus hunters. After exhausting routine diagnostics, Pesavento sent samples to virologist Eric Delwart, a collaborator on numerous research projects over the years. His team at Blood Systems Research Institute in San Francisco ran viral metagenomics and uncovered a sequence from a previously undetected virus in red pandas.

“Being curious people, that made us go down all these other rabbit holes of where did this virus come from?” said Dr. Ray Wack, who serves as the zoo’s senior veterinarian. “Is she the only red panda with this virus? Could she have gotten it from skunks in the area, as we know they carry amdoparvoviruses as well?”

Throughout their lifetimes, all living creatures are infected with numerous viruses, but not all of these persistent infections cause health problems. Most will never cause problems, and some remain latent or hidden until the immune system is compromised. Wack suspects this was the case with this first panda tested.

“We don’t know what effect this virus has on the health of animals who carry it,” Wack said. “It’s possible that it sits there and doesn’t become active until their immune system is compromised.”

During his residency in anatomic pathology, Alex took on the project to characterize infections with this amdoparvovirus, which falls in the same family as the more widely known canine parvovirus and feline panleukopenia virus. Skunks, raccoons and gray foxes all carry various types of amdoparvoviruses.

He also needed to determine whether it was prevalent in other pandas and if it posed a health risk to captive populations. Based on the metagenomic results provided by Delwart, Pesavento’s lab team was able to develop PCR diagnostics to test other pandas, starting with those at the Sacramento Zoo. Based on their tests, all of the Sacramento pandas did carry and shed the virus over a long period of time, although they didn’t exhibit any clinical signs of disease.

“That tells us it is a persistent virus in these animals, but not necessarily always a cause of disease,” said Alex, who is now midway through a one-year pathology fellowship and plans to continue this research for his Ph.D. “Why it seemed to be involved in the first case is unclear. In no other animals have we found similar inflammatory lesions as a result of this virus.”

Because red pandas are frequently moved among zoos to provide the best possible matches for breeding through the Species Survival Program, researchers felt it was important to test the wider sample of red pandas in zoological institutions. That project is currently underway and Alex estimates they will complete that step by this summer.

The project is a collaboration with zoos across the country and with Dr. Steven Kubiski from San DiegoZoo Global, which has funded Alex’s current research position. Kubiski, who completed his graduate training and residency at UC Davis in Pesavento’s lab, is a researcher and pathologist focused on global conservation efforts for zoo and wildlife species.

“This project really highlights the collaboration between the Sacramento Zoo, San Diego Zoo Global and the UC system,” Wack said. “We’re able to make a clinical observation, take it to the pathology lab and come up with a brand-new virus that played a role in the disease of one animal, relate that to other animals at the zoo and red panda populations as a whole. With the information we’re gathering now, we’ll be able to make recommendations to the Species Survival Program on whether this is a health issue to be considered for breeding management strategies.”

One of the surprising things for Alex to learn as he embarked on this project was how red panda captive populations are managed. There is a fair amount of movement of individuals among institutions to manage their breeding based on a relatively small founding population.

“The dynamics among zoos are interesting,” Alex said. “We have a detailed record of animal movement, shared spaces, and familial relationships. It also muddies the water for us. Trying to untangle where these viruses originated is going to be tricky.”

Alex is also working on growing the virus in cell culture to better understand pathogenesis and disease association. That would be helpful for figuring out the significance of infection for an animal.

“There’s a lot we don’t know yet, but it’s an important and cool puzzle!”

Read more about viral diseases and their impact on conservation in a blog post by Dr. Steven Kubiski for the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research.