Interdisciplinary Teamwork and First Time Surgery at UC Davis Gives New Hope for Dog with Complicated Megaesophagus

“Case of the Month” – January 2023

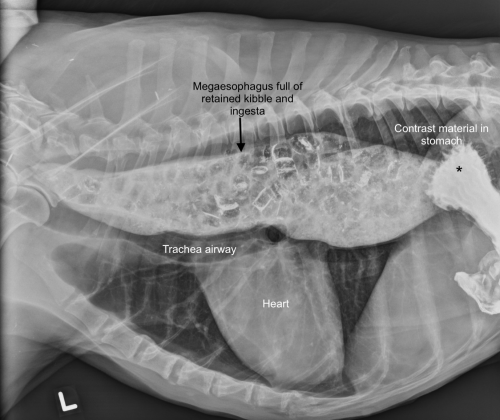

Megaesophagus, an abnormally dilated or giant esophagus, is one of the most devastating conditions a dog and its family can experience. It is a disorder in which the muscles of the esophagus (eating tube) lose tone and cannot move food and water normally from the throat to the stomach. This causes retention and regurgitation of ingesta, which can lead to inflammation to the lining of the esophagus (esophagitis), inhalation of food or water contents into the airways (aspiration), and malnutrition. Megaesophagus is a challenging disorder to manage, and the journey can be long and arduous. Thankfully for Ginger, a 13-year-old Belgian Malinois, she has a dedicated family and a compassionate medical care team diligently working to improve her quality of life. Refusing to give up hope, her team trialed several innovative medical and therapeutic procedures before opting for a surgery never performed at the UC Davis veterinary hospital that ended up saving Ginger’s life.

Ginger was first diagnosed with megaesophagus seven years ago when she presented with severe weakness from myasthenia gravis, a neurological disease that affects the signal transmission between the nerves and muscles. Her megaesophagus was thought to be a consequence of the myasthenia gravis. With aggressive medical treatment, the hospital’s Neurology and Neurosurgery Service supported Ginger back to health and her myasthenia gravis went into remission. However, the megaesophagus persisted until it became life-threatening.

By December 2020, Ginger was experiencing painful regurgitation episodes with every meal, and she had lost more than 15 pounds at which point she was presented to Dr. Tarini Ullal in the Small Animal Internal Medicine Service. A videoendoscope (scope camera) showed significant inflammation of Ginger’s esophagus, and a swallow fluoroscopic study (video x-ray) of her swallowing food and water, followed by an esophageal catheter pressure study (high resolution manometry), showed that her lower esophageal sphincter, which connects the esophagus to the stomach, was not relaxing properly to permit passage of ingesta into the stomach.

“When a dog swallows water or food, the lower esophageal sphincter should relax spontaneously as part of a mechanized reflex or response,” said Dr. Stanley Marks, a professor in small animal medicine, and board-certified specialist in internal medicine, nutrition, and oncology with advanced expertise in gastroenterology and esophageal disorders at UC Davis. “This was not happening with Ginger. Therefore, we suspected she had a condition called esophageal achalasia-like syndrome.”

Achalsia-like syndrome is a disorder that has been well characterized in people but is far less characterized in the dog.

A series of diagnostic and therapeutic tests confirmed this diagnosis, and a stomach feeding tube was placed in Ginger to temporarily circumvent the dilated esophagus while her extensive care team started a series of medical treatments and procedures to treat the condition.

In addition to Drs. Marks and Ullal from the Small Animal Internal Medicine Service, a collaborative ensemble from the Diagnostic Imaging, Nutrition, Anesthesia, and Soft Tissue Surgery Services joined forces to find a solution. The team also consulted with physicians from UC Davis Health and Sutter Health to further explore a more permanent therapeutic approach for Ginger.

“This was an incredible group of people who were motivated and passionate to work together and find a solution for Ginger,” said Dr. Ullal, who completed the Purina Gastroenterology and Hepatology Fellowship at UC Davis under the mentorship of Dr. Marks. “Her owners also showed immense commitment, devotion to her care, and tremendous resilience as we trialed different treatments and interventions.”

A series of treatments targeted at reducing the pressure in the restricted lower esophageal sphincter were attempted. First, a medication called sildenafil was used to relax the sphincter, but minimal response was seen. Next, balloon dilation and botox injections of the lower esophageal sphincter were attempted to open and relax her lower esophageal sphincter. Despite these efforts, the sphincter remained abnormally constricted.

Reaching this point of treatment is rare in veterinary medicine. In humans that do not respond to these interventions, the next option is a surgical procedure to help open the sphincter. Thus, further opinions and consults were sought from the UC Davis School of Medicine and Sutter Health esophagologists and surgeons to better understand the surgical approach, and by July 2021, Ginger became the first UC Davis veterinary patient to ever have the esophageal procedure.

Ginger’s surgery involved a myotomy, which involves cutting through the musculature of the lower esophageal sphincter, and also a fundoplication, which involves partially wrapping the stomach around the lower portion of the esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter to reinforce the connection of the esophagus and stomach. The fundoplication step was necessary to prevent overrelaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, which could have caused more reflux and regurgitation.

“It was a delicate procedure because the lower esophageal sphincter musculature had to be incised enough to relax the sphincter, but the stomach also had to be oriented to add tone back to the esophagus-stomach junction without overtightening and re-creating an obstruction,” said Dr. Marks.

This technique has only been performed in a handful of dogs with conditions similar to Ginger’s and therefore the long-term rate of success is not known. For Ginger, the surgery combined with sildenafil treatment to relax the sphincter has been a remarkable success. She is now able to eat a liquid diet by mouth when fed upright, and she remains well controlled 18 months post-surgery.

Ginger’s family reports that she, like most dogs with megaesophagus, has adapted well to her new diet and is eager to get into her specially designed feeding chair for meals.

Drs. Marks and Ullal emphasize there is still much more to be learned about esophageal achalasia-like syndrome and megaesophagus in dogs. Dr. Marks and Ullal have now launched ongoing clinical trials at UC Davis to better understand, characterize, and treat megaesophagus and other similar disorders in dogs. The team hopes that Ginger’s case is just the beginning of finding new paths to treat dogs with this condition.

“With a team of really creative and collaborative individuals, we were able to help Ginger,” said Dr. Ullal. “We restored Ginger’s quality of life and met her family’s goals in a significant and impactful way. We now hope to apply our learnings from Ginger’s case to help many more dogs.”

# # #