Uncovering Secrets to Feline Longevity

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2023 issue of CCAH Update.

Contrary to the proverb that cats have nine lives, our feline companions only have one. So, it’s important to understand what drives longevity, disease and death so that we can help provide as many quality years as possible.

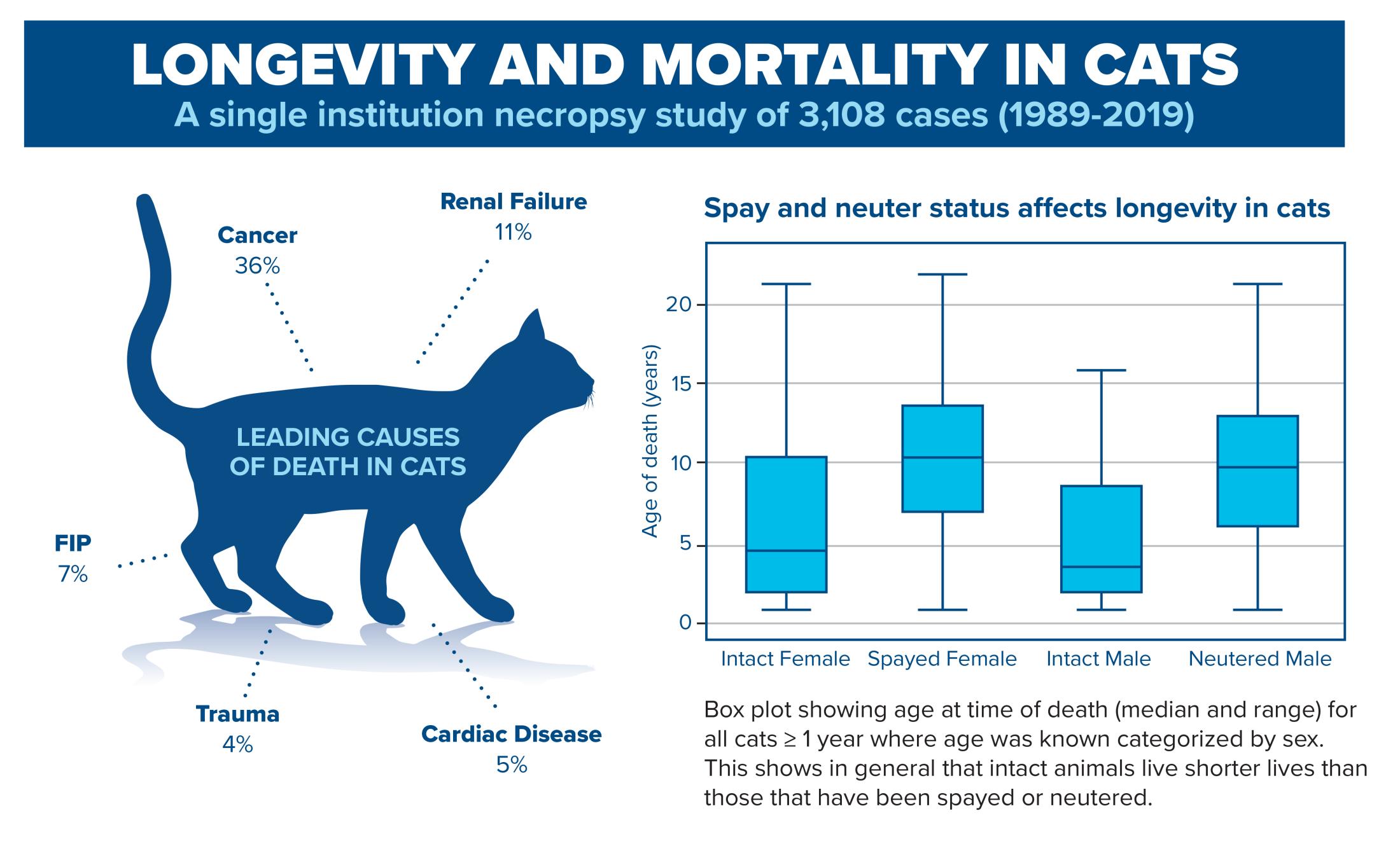

UC Davis veterinary researchers, led by CCAH Director and radiation oncologist Dr. Michael Kent, embarked on a multi- year investigation through the school’s extensive electronic medical record system to find answers. Their study, published in the scientific journal PLoS One, examined the cases of more than 3,100 client-owned cats (85% of them mixed breed) who underwent a necropsy – or post-mortem examination – at the UC Davis veterinary hospital between 1989 and 2019. They examined demographic and environmental factors, age, cause of death and spay/neuter status – information that wouldn’t normally appear on a pathology report that may provide additional insight.

“We were really surprised to discover that intact cats of both genders had significantly shorter life spans,” said Kent. “That’s a huge finding.”

Overall, the median age of death for intact females was 1.5 years, but that included kittens who may have been born with a congenital disease and didn’t have the chance to be spayed, so the researchers reevaluated the data to remove cats under one year of age. For intact female cats older than 12 months, the median age of death was 4.7 years compared to 10.5 for spayed females. For intact males over the age of one year, the median age of death was 3.7 years compared to 9.8 for their neutered counterparts.

“These are very significantly different median ages of death and also show the high cost of reproduction for females,” Kent said. “We knew that cats get cancer, renal and heart disease, but we wanted a clearer picture of what may impact disease process or contribute to longevity.”

The study revealed that cancer was the cause of death in more than 35% of cases, although it was identified in 41%, so it didn’t cause death in all cats with cancer. Approximately one-third of the cats had one cancerous tumor, 146 had two tumors, and there were a few cases with up to five tumors.

“As an oncologist, the percentage of deaths attributed to cancer didn’t surprise me,” Kent said. “We see a lot of those cases, so we have a bit of a skewed population.”

Perhaps a bit more surprising was the percentage of cases with renal disease.

“Kidney abnormalities were present in nearly 63% of cats in the study,” said Dr. Patricia Pesavento, a member of the team. “While primary kidney disease was responsible for killing 13%, co-morbidity [the presence of two of more diseases] could affect the quality of life or increase susceptibility to other diseases in many more cats. The question is what causes renal disease in cats? What can we do about that?” The CCAH is dedicated to answering these questions.

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) remains a significant cause of mortality in young cats and was responsible for approximately 1 in 20 deaths in the study. Fortunately, large collaborative teams at UC Davis are on the forefront of curing FIP with two clinical trials currently underway. Another interesting finding was that indoor/outdoor cats did not have a significantly shorter lifespan than indoor-only cats. Outdoor-only cats did have a shorter lifespan.

Generous CCAH donors helped strengthen the electronic medical records database in recent years, making this type of retrospective study possible. Still, poring through three decades of data on more than 3,000 cats is labor intensive. Kent credits the dedication and diligence of the team comprised of Drs. Bill Culp (surgeon), Amandine LeJeune (medical oncologist), Pesavento (pathologist), Christine Toedebusch (neurologist), Rachel Brady and Robert Rebhun (oncologists), as well as veterinary student Sophie Karchemskiy—who is now a DVM intern at The Animal Medical Center in NYC. Participating in this study under Kent’s mentorship helped Karchemskiy further her research skills.

“Every member of a collaborative team like this plays a significant role,” Kent said. “Time and again, scientific discoveries show that teams work better.”