One Health

Finding crucial linkages among animals, humans and the environment helps to solve complex zoonotic disease, food safety and environmental challenges from the molecular to the ecosystem levels. The One Health approach accepts the interconnectedness of different species and their shared habitats, requiring faculty from many disciplines working in concert to optimize outcomes.

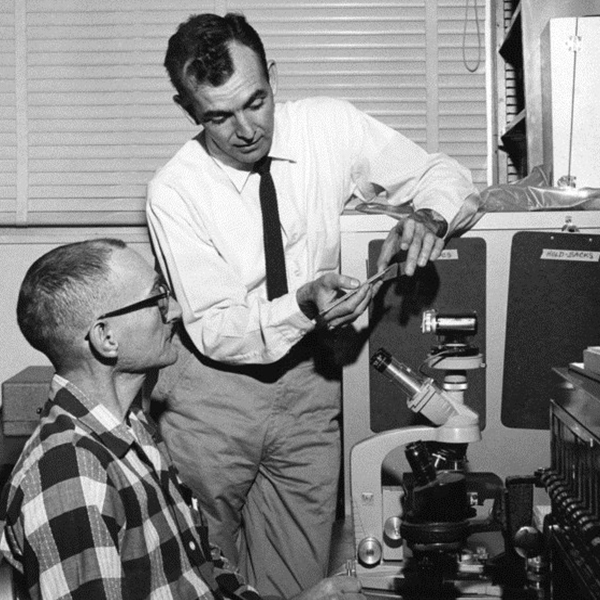

Thanks to the inspiration and vision of faculty pioneers in One Health, veterinary students since the 1960s have learned to apply the principles of epidemiology, microbiology, virology and other disciplines to veterinary public health and food safety.

Seminal publications in the 1950s revealed that bats carry rabies; later studies illuminated the biology, environment, pathogenesis, hibernation and other factors aimed to prevent or reduce disease after an exposure. One researcher also reviewed the effectiveness of rabies vaccination techniques in humans.

Faculty described the ecology of Q-fever and how it passed from livestock to people. These scientists shone a light on tuberculosis, listeriosis and other zoonotic diseases, accomplishments that have improved food safety and helped safeguard public health since 1948.

In 1987, faculty expertise in clinical diagnosis became fully integrated with California's Department of Food and Agriculture when the California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory System moved to the school under faculty direction. These partners have served agricultural producers and California consumers directly with diagnostics and health management of food animal herds, poultry flocks, equines and even wildlife as it relates to human and environmental health.

Over time, the de facto One Health approach became an explicit part of the school's mission, and in 2009 the One Health Institute was founded to organize the school’s principal One Health activities. This integrated approach has influenced even the location and layout of the Veterinary Medicine 3A and 3B facilities. Their open-concept laboratories foster greater interaction among basic and clinical faculty as well as students.

During the 1990s, the epidemiology of waterborne zoonotic pathogens such as Cryptosporidium outlined influences on the transport of the pathogen as well as risks from wildlife and livestock near water supplies. The data now help decision-makers devise beneficial management practices for microbial food safety and environmental quality.

Environmental contaminants affect animals and people. For example, faculty affiliated with the Aquatic Health Laboratory and the Center for Health and the Environment have shown how even common chemical compounds may alter reproduction, brain function and cancer in different species, including humans.

To aid in coordination of the science involved in complex health issues, the school's One Health Institute works with the UC System, state and federal agencies and partners throughout the world. As one example, the Health and Livelihood Improvement Program, HALI, monitors how the quality of scarce water supplies shared among people, livestock and wildlife create impacts on human health and family livelihoods in Tanzania.

Since 1998, the Center for Comparative Medicine, a joint program with the School of Medicine, has explored persistent diseases shared by animals and people; center faculty were involved in the development of the first federally approved Lyme disease vaccine and a greater understanding of the chronic nature of the disease. Immune responses to influenza and drug resistance in retroviral diseases are other significant areas of study where progress has been made.

The school's demonstrated track record in veterinary medicine, science and environmental health was instrumental in the awarding of the USAID grant for PREDICT at the school. This global surveillance program identifies wildlife pathogens that may be transmitted to humans in disease hot spots in more than 20 countries around the world. In 2014, using the results of PREDICT's early diagnostic testing of Ebola samples in the Democratic Republic of Congo, that government enacted immediate measures to successfully contain the disease in that region.

The One Health commitment is reinforced by the Mouse Biology Program and other animal model resources that closely align to human health. Since 95% of the mouse genome is similar to that of humans, biomedical researchers employ genetically modified mice to study complex disease processes, genetic defects and the efficacy of new drugs. The program provides resources to scientists around the world. Society has also benefited from air quality standards recommendations and other advances in pulmonary health that rely on the non-human primate-notably, at the California National Primate Research Center-to study human lung development, asthma, influenza and other human health issues.

Joint ventures with the School of Medicine provided extraordinary opportunities to tackle critical issues together. Clients who enroll their animals in the Veterinary Center for Clinical Trials may choose special treatments for their pets while helping confirm the efficacy of new cancer drugs, pain medications and other pharmaceuticals in humans. In 2013, the National Cancer Institute acknowledged the program's “unique and noteworthy scholarly contributions in the field of cancer drug development.”

For veterinary students, participating in the Zoobiquity conferences with medical students the One Health communications awareness of the "species-spanning nature of illness" is invaluable in promoting the benefits of cross-pollination of scientific ideas for future collaborators.