How Stories Can Save Our Planet and Ourselves: A Q&A with the Authors of Belonging to Earth

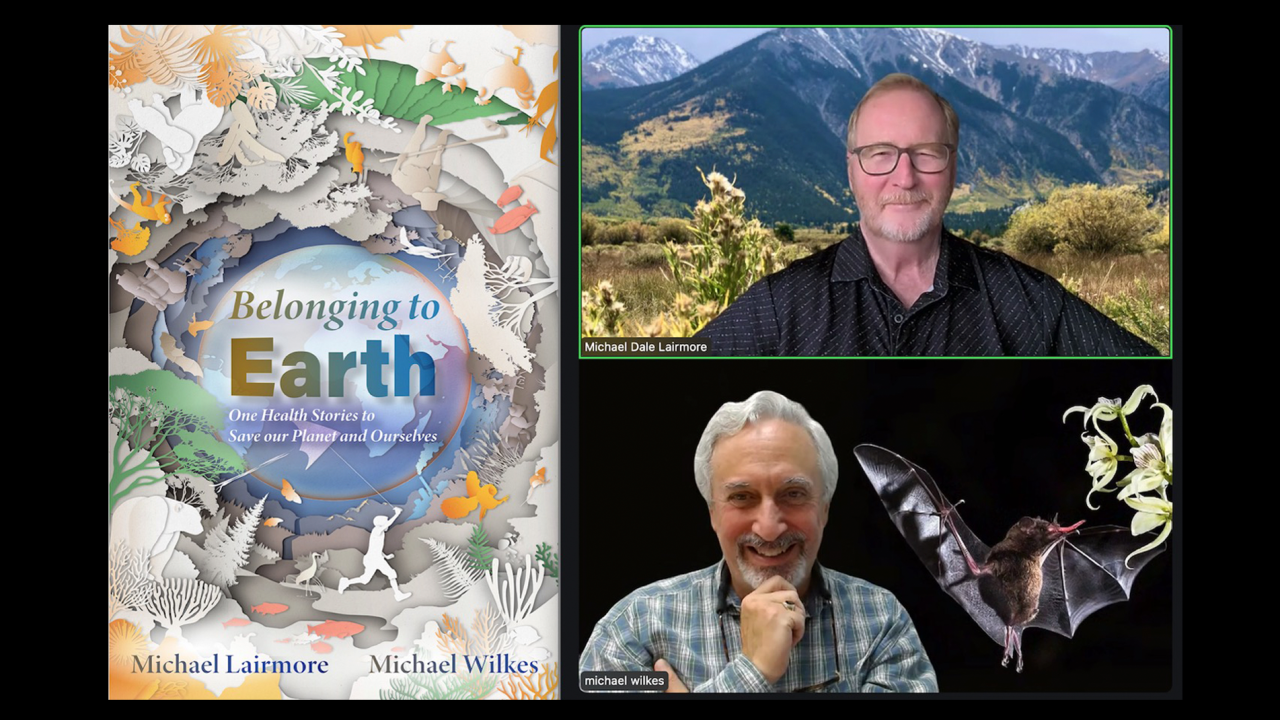

Dr. Michael Lairmore and Dr. Michael Wilkes—two UC Davis-affiliated thought leaders in veterinary medicine and global health—have just released a new book, Belonging to Earth: One Health Stories to Save Our Planet and Ourselves (Cambridge Scholars Publishing). Lairmore is dean emeritus of the School of Veterinary Medicine. Wilkes is director of global health and professor of medicine at the School of Medicine, and senior medical correspondent for KCRW/NPR. In this conversation, they reflect on why storytelling is vital to the One Health movement, how UC Davis helped shape the book, and what a One Health future could look like.

Q: What inspired you to write this book now?

Lairmore: We realized that when we explained One Health with definitions and diagrams, it didn’t always land. But if we told a story about a community facing disease, an environmental issue that affected animals and people—that clicked. So, we wrote a book built around stories with real stakes.

Wilkes: One Health is this idea that everything is connected to everything else. So to address a health problem, you really have to break it down into its component parts. We felt like no one was telling the story of One Health in a way that resonated with the public. It’s often presented as academic or abstract, but it's really about people’s lives. Stories bring that to life.

Q: How does the book reflect your UC Davis experiences?

Lairmore: Many of the chapters originate from UC Davis programs—Knight’s Landing One Health Clinic, the One Health Institute, even our veterinary hospital. The "Deadly Blooms" chapter, for example, draws on real environmental health issues we’ve tackled here.

Wilkes: We also developed a curriculum that brought together medical and veterinary students. It turned out to be one of the most popular programs in the medical school. Students saw firsthand how important it is to collaborate across disciplines to solve real-world health challenges.

Q: One Health has gained more visibility in recent years. Why do you think that is?

Lairmore: The momentum is real. Major institutions like the WHO and CDC now have One Health offices. Universities across North America have joined a One Health network. It’s no longer a fringe idea—it’s central to solving 21st-century problems.

Wilkes: I started working on One Health nearly 20 years ago, when most people hadn’t heard of it. Now, we see diseases like Lyme or hepatitis A being recognized not just as environmental or medical issues—but as One Health issues. That’s real progress.

Q: Can you give an example of how stories in the book reflect current headlines?

Lairmore: The “Deadly Blooms” chapter I mentioned is about harmful algal blooms. Just this week, the CDC was hosting briefings on the same topic. These blooms affect water, ecosystems, pets, and human health—and our chapter looks at how climate, agriculture, and public health are all part of the picture.

Wilkes: Another chapter focuses on refugees. That story touches on the human, environmental, and animal health impacts of displacement—topics we’re seeing daily in the news, whether in Gaza or other crisis zones.

Q: Do you see this book as a series of blueprints for addressing situations with a One Health approach?

Lairmore: Every situation is different so it’s more of a learning guide than a blueprint. In the chapter on feral cats and wildlife conservation, for example, we show an approach and also how both sides have valid concerns. It’s not about picking a side—it’s about understanding the bigger picture and the consequences of our choices.

Wilkes: Honestly, most of our stories don’t have neat endings. That’s intentional. We want readers to see the complexity, the trade-offs. Policies have winners and losers—sometimes human, sometimes animal, sometimes ecological.

Q: What’s your vision of a One Health “utopia”?

Lairmore: It starts with education. From a young age, kids should learn to value nature, biodiversity, and animals as part of a shared system. Stewardship needs to be second nature.

Wilkes: I lived in Rwanda for a few years, and saw an effective model: a government-wide One Health secretariat where ministers of health, agriculture, education, and tourism met monthly. That level of coordination made a real difference. We need systems that reward cooperation—not just individual excellence.

Q: Who can benefit from reading this book?

Wilkes: Everyone. We want it to speak to someone in high school, a policymaker, a farmer, a physician, a pet owner—anyone who cares about the world they live in.

Lairmore: If it helps people realize that our problems—and solutions—are interconnected, and that One Health isn’t a specialty but a perspective, then we’ve succeeded.