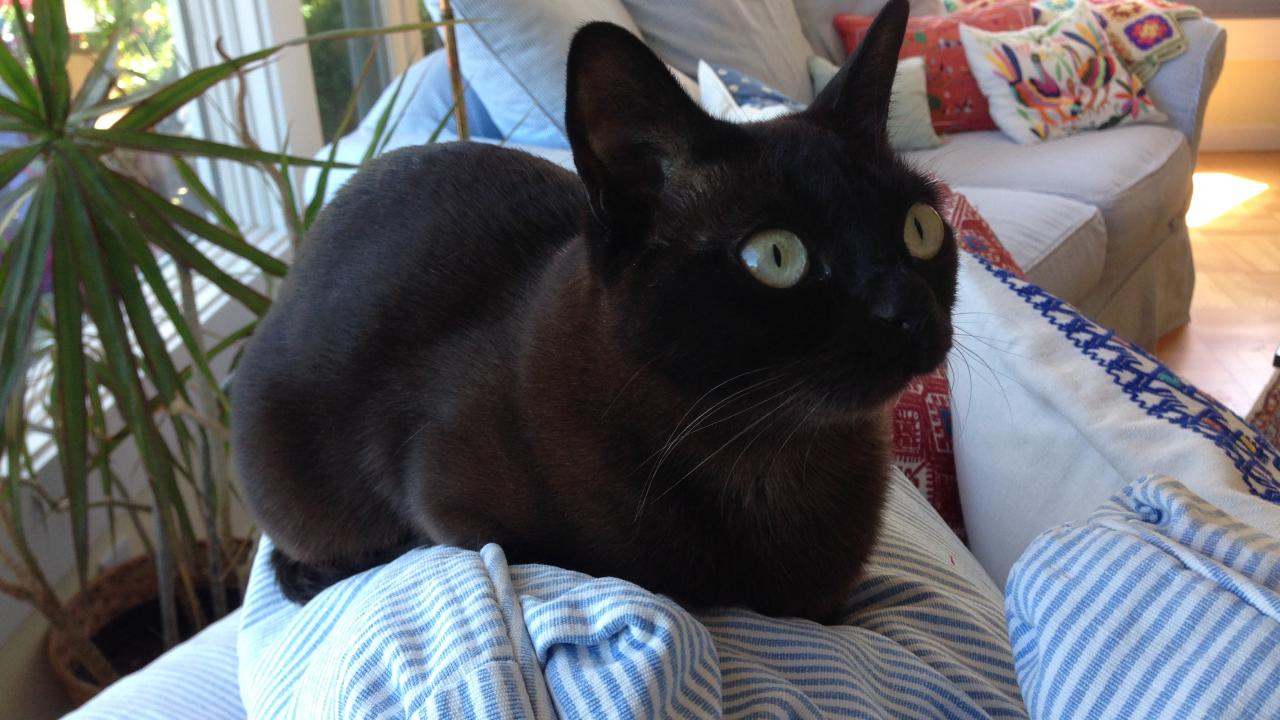

UC Davis Performs Extremely Rare Heart Surgery to Save Cat

May 14, 2015 - Vanilla Bean, a 1-year-old female Burmese cat from Mill Valley, California, was brought to a veterinary cardiologist for respiratory distress. That vet, Dr. Kristin MacDonald, DVM, PhD, DACVIM, diagnosed her with a rare congenital heart defect that does not allow blood to flow properly through the chambers. This improper flow can cause too much blood to collect in one chamber, create pressure, enlarge it, and ultimately lead to congestive heart failure.

Dr. MacDonald, a former UC Davis cardiology resident, was familiar with a procedure to correct the defect. A special technique for correction has been reported only once before by Dr. Josh Stern, DVM, PhD, DACVIM, when he was practicing at North Carolina State University. Luckily for Vanilla Bean, Dr. Stern has since joined the faculty of the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital (VMTH) at UC Davis. Instead of being 3,000 miles away, the possible answer to Vanilla Bean’s problem was less than 100 miles away. So Dr. MacDonald contacted Dr. Stern, and started the process of referring the case to UC Davis.

Once at UC Davis, Dr. Stern and his team of residents, technicians and veterinary students evaluated Vanilla Bean by performing an echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart) to assess the severity of her heart disease and to see if she is a good candidate for surgery. They were able to confirm Dr. MacDonald’s diagnosis and move forward with a plan for correction.

The mammalian heart is comprised of four chambers. In a normal heart, blood flows from the upper collecting chambers (atrium) into the lower pumping chambers (ventricle) by passing through valves. On the left side of the heart, this valve is called the mitral valve. Cor triatriatum sinister, with which Vanilla Bean was diagnosed, is a disease in which there is an abnormal sheet of tissue that lies above the mitral valve causing a restriction of blood flow traveling from the upper chamber into the lower chamber of the heart, termed stenosis. This abnormal tissue creates a build up of pressure and causes fluid to build up in the patient’s lungs, termed congestive heart failure. In Vanilla Bean’s case, the abnormal tissue and stenosis occurs somewhere in the middle region of the atrium (collecting chamber), dividing it into two portions. In order for blood to flow from the atrium into the ventricle (pumping chamber), it must travel at a faster velocity in order to get past the narrowed and thickened region. The portion of the upper atrial (collecting) chamber that is above the thickened stenotic tissue begins to enlarge from an increase in pressure. As this pressure continues to rise, fluid can back up into the lungs and the initial stages of congestive heart failure begin.

Vanilla Bean’s specific type of congenital heart defect is also found in children. In the only previous procedure Dr. Stern performed to correct this condition, he collaborated with human cardiologists from Duke University, near where he was practicing at North Carolina State. To help assist him again, Dr. Stern sought out two cardiologists from the UC Davis Medical Center.

“I needed a human cardiology team to help guide me on this case, as well,” said Dr. Stern. “It’s so uncommon in cats. It’s uncommon in children also, but they’ve certainly seen more cases of this than I have.”

During their training at the VMTH, third-year veterinary cardiology residents spend a few weeks with human cardiologists at the UC Davis Medical Center. Through this connection, Dr. Stern was acquainted with whom he needed to assist him with Vanilla Bean’s surgery. Dr. Jeff Van Gundy, MD, a clinical professor of pediatrics who specializes in cardiology, and Dr. Jay Yeh, MD, an assistant professor of pediatric cardiology with a special interest in echocardiography, were brought in to assist Dr. Stern. Rounding out the team was Dr. Bill Culp, VMD, DACVS, a soft tissue surgeon at the VMTH and Dr. Lance Visser, DVM, MS, DACVIM, a cardiologist at the VMTH.

Together, these five doctors began the delicate procedure of opening the stenosis with a hybrid cutting balloon dilatation. Normally, if this were an animal with bigger vessels, the surgery would have been performed through catheters and approached the heart without opening the chest cavity. Since a cat’s vessels are too small to utilize in that manner, a more invasive approach had to be taken.

Dr. Culp opened Vanilla Bean’s chest cavity to expose the heart, and Dr. Van Gundy and Dr. Stern began the delicate process of positioning the catheters and balloons within Vanilla Bean’s heart. Drs. Yeh and Visser, through transesophageal echocardiography, helped Dr. Stern visualize where he was in the heart and monitored the success of each technique that was utilized.

“This is an extremely uncommon technique employed in veterinary medicine,” said Dr. Stern. “It’s even more rarely employed in cats due to their small size.”

With further help from Dr. Culp to position the balloon in the correct place, Dr. Stern was able to place the balloon across the defect. The balloon cuts the membrane to allow blood to flow through it regularly.

While the balloon dilatation was successful, Vanilla Bean’s surgery was not without complication. She lost a lot of blood during the procedure. Luckily for Vanilla Bean, the VMTH operates the largest veterinary blood bank in the western United States. Her transfusions were swiftly performed with blood from the hospital’s feline donor base.

Due to the blood loss, though, Vanilla Bean suffered an acute kidney injury. Her creatinine levels spiked to dangerously high levels following the procedure while she was recovering in the VMTH’s Intensive Care Unit. Dr. Stern was concerned she would die of kidney failure. Over the course of a week being hospitalized, however, those levels slowly decreased every day.

Vanilla Bean was able to go home eight days after her surgery. A week later, she returned to the VMTH for a check-up. Her creatinine levels, while still not in the normal range, continued to drop. An echocardiogram showed the pressure in her heart had not changed since the reduced pressure was measured during the surgery, which meant the balloon dilatation was successful.

At her four-month re-check examination, Vanilla Bean has continued to improve. She is no longer in congestive heart failure, and is off all medications. Her creatinine levels have returned to the normal range. Dr. Stern expects her to make a complete recovery, as she appears to be on the road to a healthy life.

# # #