Bryce Westbrook

My two-week externship at Utrecht University was nothing short of extraordinary. I had the incredible opportunity to complete a two-week externship at Utrecht University and rotate through their Avian & Exotics service as well as their Internal Medicine service. This was a transformative experience, and I learned a tremendous amount during my brief time there.

The first week of my rotation was a whirlwind of exotic creatures and furry friends. In the Avian & Exotics service, I found myself working alongside fellow students from Utrecht University, eagerly diving into the intricate world of parrots, rabbits, guinea pigs, and hedgehogs. What struck me most was the opportunity to connect with the owners, who entrusted us with the care of their beloved pets. Taking charge of some cases allowed me to feel like an integral part of the team, whether it was unraveling the mysteries of a hedgehog with a potential pyometra or devising a plan to restore a parrot's lost appetite. Every day brought new challenges and learning opportunities, and I cherished the chance to make a difference in the lives of these unique creatures.

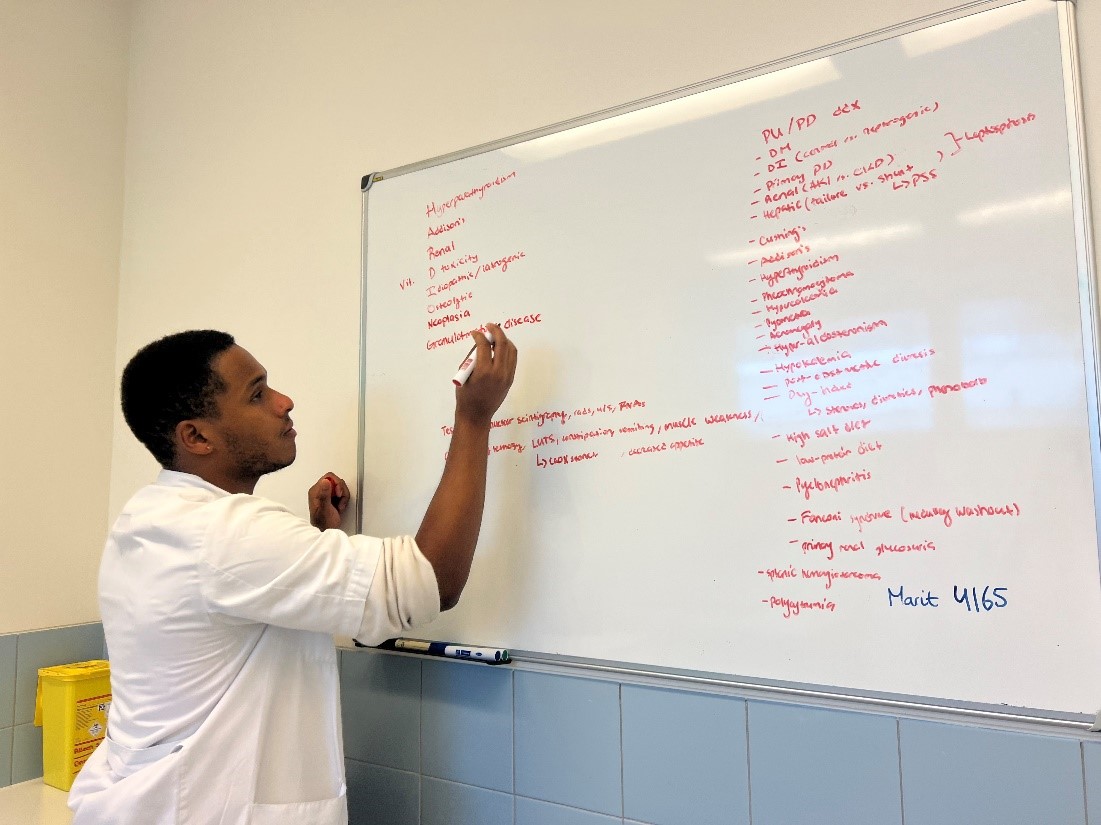

The second week was a deep dive into the world of Internal Medicine but with a European twist. Unlike my experiences at UC Davis, Utrecht University's Internal Medicine department was divided into subspecialties, offering a comprehensive look into the intricacies of veterinary care. Over the week, I delved into nephrology, hematology, neurology, endocrinology, and gastroenterology. Collaborating closely with fellow students, I shared my knowledge and eagerly absorbed their insights. The cases I encountered ranged from a domestic shorthair cat battling chronic kidney disease to a lively Pitbull with polyuria/polydipsia and a delicate Yorkie experiencing pain when turning her head. Each case was a puzzle to solve, a chance to apply what I had learned, and a reminder of the profound connection between animals and their caregivers.

Beyond the clinical experiences, my externship was a journey of cultural enlightenment. Stepping into a foreign country, I realized the need to shed preconceived biases and embrace the rich tapestry of veterinary medicine in Europe, distinct yet undeniably intertwined with my experiences in the United States. This transformative experience reinforced the importance of approaching medicine with an open mind and acknowledging the shared principles and subtle distinctions that shape European veterinary practices.

The impact of this journey on my life and career cannot be overstated. It ignited a fervor for internal medicine, especially the specialized realm of endocrinology. This externship deepened my commitment to the field, reaffirming my desire to make a meaningful difference in the lives of animals.

I owe immense gratitude to Global Programs, Utrecht University, Dr. Beaufrere, and the invaluable support of Daniel and Maggee. Without their collective efforts, this life-altering experience would not have been possible. As I stand at the crossroads of my journey, I carry with me a wealth of knowledge, a heightened cultural awareness, and a renewed fervor for veterinary medicine. With boundless enthusiasm, I look forward to the future, ready to embrace the challenges and opportunities ahead.