Anne Werum

This summer, I completed a 6-week mixed-animal clinical externship in Germany. I interned at the Pferdeklinik und Kleintierpraxis in Maichingen, a small animal general practice and equine clinic with an emergency service. While the clinic routinely worked with dogs, cats, and horses, the veterinarians also treated guinea pigs, sheep, and camelids. One of my favorite appointments was a visit to an alpaca farm, where we performed some general wellness exams and even x-rayed one alpaca, who was circling to the right—it turned out because of a fusion of C1 and C2 from an old injury.

In addition to learning more about species I had not worked with before, this externship was a great opportunity for me to learn about equine medicine and how it could fit into a mixed animal practice. At this clinic, they had three small animal veterinarians, two large animal veterinarians, and two more recent graduates who worked with small and large animals. The two mixed animal veterinarians would have some days in the small animal practice, and some days on large animal field service. Since I am still deciding between small animal and equine medicine, I am grateful to have gained insight into what the day-to-day life looks like for recent graduates in this kind of clinic.

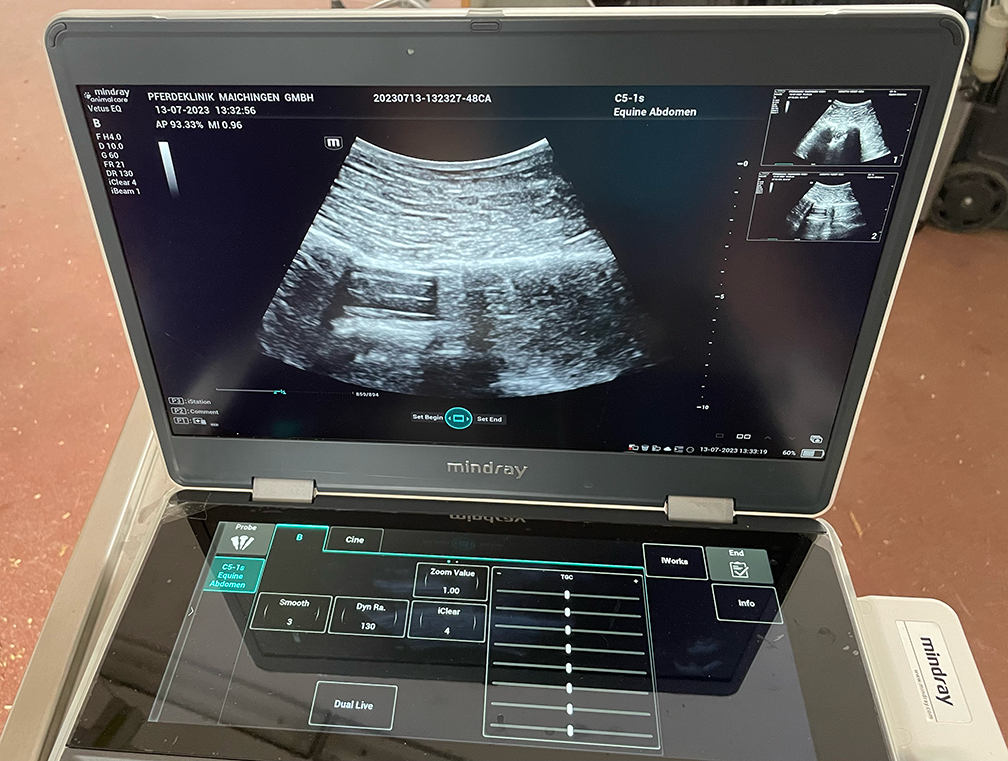

Since I had more previous small animal experience, I spent most of my days in the equine clinic. A typical day would consist of one longer appointment in the morning, and shorter field service visits in the afternoon. In the mornings, we often had extensive lameness exams that would be performed in the clinic. We would start with observing the horse at a walk, trot, and in the ring, mostly using the lameness locator. After that, we took thermography images of the whole horse to help localize the lesion to a specific site within the lame limb or back. Next, we would take radiographs and perform an ultrasound. I enjoyed being able to attempt a lameness diagnosis for myself before discussing it with the clinician and incorporating our other diagnostics. In addition to lameness exams, I also learned to assist with endoscopy and had time to practice my ultrasound of the metacarpal tendons and ligaments, as well as the spinal cord between C1 and C2. While it was exciting to be a part of these procedures, one of the most important skills I learned was how to handle difficult horses in a clinical setting. This gave me a more realistic idea of equine practice and the dangers and joys associated with it.

Not only did I learn a lot about veterinary medicine, I was also able to witness how culture influences the interactions between veterinarians and clients. When shadowing the interactions between German veterinarians and their German clients, I noticed how the veterinarians’ directness was not only tolerated, but it was also usually appreciated. The veterinarians were very good at refraining from sugar-coating the severity of an injury without upsetting their clients, a skill I hope to incorporate in my own communication.

Along with the influence of German directness, I also witnessed the effects of rural culture on the practice. Since the clinic was located in a more rural part of Germany, a lot of the technicians had been there for years and most knew each other personally or were even related. One of the veterinarians had even been a tech at this clinic and had returned after vet school. During our lunch breaks, the technicians would usually play card games together and invited me and the other intern to join them, which gave the practice a very welcoming small-town feel. Not only did I learn a lot, I also very much enjoyed the time I spent there!